February 18, 2025

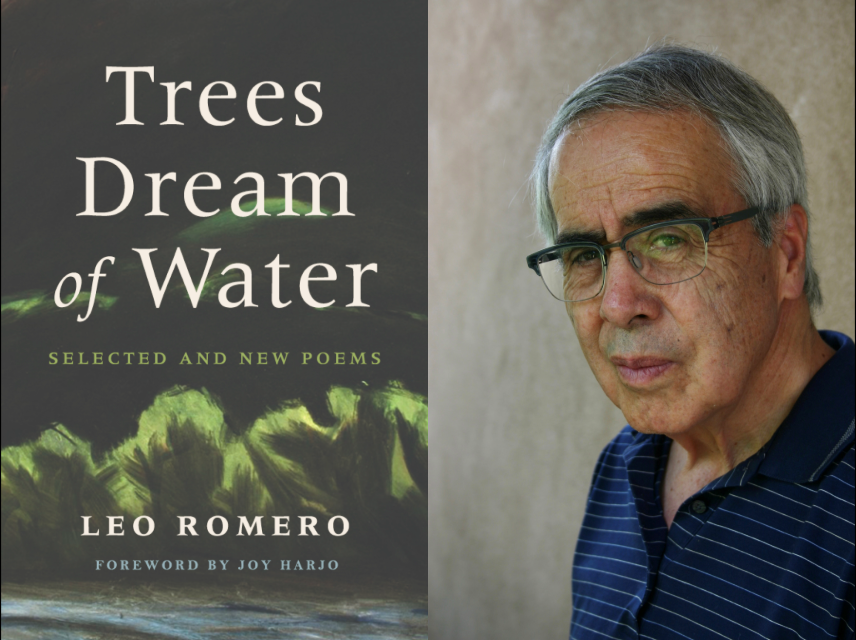

Leo Romero stands as a foundational figure in Latino letters. With six books of poetry and a book of short fiction to his name, Romero’s contribution to the literary canon is profound and enduring. Bringing together for the first time his new and selected poems, Trees Dream of Water: Selected and New Poems reflects Romero’s journey from youth to maturity as a person and a poet, and his deep connection to New Mexico and its culture. Today, the author answers five questions (plus one bonus question!) about his work, process, and career.

This collection spans decades of your work alongside new poems. Looking back, do you feel your writing has changed dramatically since you began publishing, or are there elements of your work that have persisted since the beginning?

Trees Dream of Water are poems from the seventies and eighties. Five books were published from 1978 to 1991. After that, I basically stopped sending poetry (in book form) out for publication.

I stopped sending out manuscripts, but I didn’t stop writing. Writing is something I do naturally. It’s not something I think about doing. It’s just another thing I do in my life, ideas come to me, and I go with them. For a long time, I was happy with just writing and then not thinking about doing anything with the poetry. Over a few months I’d get engaged with a subject, and at the end I’d have a collection of 60-80 pages. But I would do very little (if any) editing to the poems. I would leave them on my computer as a file, and then I would get engaged in doing another collection of poems. Eventually I had many of these collections, and the thought of going back to edit them seemed daunting. So the poems have been languishing as files that I haven’t looked at for a long time. Many years back, the University of New Mexico established an archive for my poetry. Early on, I got them some material, but as my collections of poems kept piling up, I found the thought of editing those poems, those collections, and getting them to my archive too time consuming.

A friend I hadn’t seen since the seventies, Joy Harjo, stopped in my bookstore about three years ago and immediately said, “Leo, why aren’t you publishing!” She woke me up to the fact that I should put together a new manuscript. I edited some older poems and called the collection Beyond Nageezi. That was sent to the University of Arizona Press, and then somehow the idea came about to do my new and selected poems as a book. If not for Joy’s encouragement, I suspect my poems were headed to oblivion as files on my computer.

With the University of Arizona publishing Trees Dream of Water, I’ve been encouraged to start editing some of those old collections, those files. I recently had a health scare but fortunately it’s turned out okay, but my thought at the time was, “I’m not going to have the time to edit many of my old poetry collections.”

Do I feel my work has changed? I feel that from the beginning, I was working towards writing poems in a series, poems that unite to form a contained world. And this really came to fruition in my book Celso. I was already writing the Celso poems from the mid-seventies and finished them in the early eighties, realizing as I was writing them that they were a continuing story with a beginning, middle, and end. That form of writing continued with Going Home Away Indian and San Fernandez Beat. I like creating a world and losing myself in it. One poem inspires another poem, inspires another poem, inspires another poem until the story comes to an end.

Now that I’m editing older collections of poems, I’m seeing that thread in those collections, a wanting to tell a complete story within the bounds of a poetry collection. As I got older, the poems became more narrative, but that had to do with the fact that I was unravelling a story. But there are still lyrical poems mixed in, the type of poems I wrote early on before I realized I could tell a continuing, closely knit story within a collection.

Rigoberto Gonzalez has dubbed you one of the “foundational poets” of the Chicano literary community. What is your reaction to this title?

I was at first surprised. But then I thought of some of my early publications, like We Are Chicanos: An Anthology of Mexican-American Literature (Washington Square Press, 1973). As far as I know, this was the first national publication of Chicano literature. In 1975, I was published in For Neruda, For Chile: An International Anthology (Beacon Press Boston), and early on I was published in the literary magazine The Bilingual Review/Revista Bilingüe (later publishing books as Bilingual Press/Editorial Bilingüe), which also published my book of short fiction, Rita & Los Angeles (1995). Then there was my book Celso, published by Arte Público Press. In 1980, Tonatiuh-Quinto Sol International (an early publisher of Chicano literature in Berkeley) published an early version of Celso through Grito Del Sol: Chicano Indo-Hispano and Mexican-American Literature. And that led to a play called I Am Celso (1985) performed by the Group Theater in Seattle, which toured around the country. And I was published in various anthologies with Latino themes such as After Aztlan: Latino Poets of the Nineties (David R. Godine, 1992).

So since around 1970, I was publishing and people were noticing enough to republish my poems in anthologies. The poems from the first two anthologies I was in had originally been published in The Thunderbird Magazine, a student literary publication from the University of New Mexico. But I didn’t know anyone who was seeing my published poems. It was like the poems were published and then, so what?

By the early nineties, I largely stopped sending poetry out for publication. Poems would sometimes appear in anthologies, but most of those poems had originally been published in literary magazines. It always surprised me that people found my poems in past publications and wanted to publish them in anthologies. Often I didn’t know anything about the selection until I received a copy of the book in the mail. It all somehow didn’t seem that real to me. So when Rigoberto mentioned that he had been aware of my work and thought of me as a foundational poet of the Chicano literary community I first felt surprised. But then I began thinking of all the poetry I had published over the years. Even though I had these credits early on, I didn’t know if my poetry had had any impact on anyone. And then Rigoberto said yes, he had been aware of my poetry and that caught my attention. I wasn’t publishing in as much of a vacuum as I sometimes thought.

In “Beyond Nageezi” you meditate on the dreamlike nature of self, desert, and memory. How has your work been shaped by New Mexico and the borderlands?

When I wrote some of the poems of the desert that are in Beyond Nageezi, I was a graduate student at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces. It’s less than an hour from the Mexican border. Something that was important for me when I was in Las Cruces was to go on on hikes in the desert, not always a smart thing to do in the hot sun. But I was drawn to the sparsity of that landscape and by the starkness of the land under a hot sun. When I had been living in Albuquerque I had been reading about the prophets in the Christian bible, about the visions they found in the desert. I sought my visions/poems in the Albuquerque desert, taking the city bus to the end of town, and then walking out into the natural environment, the sparseness of that environment, and seeking there what was within me but not apparent until I searched for it in the desert. When I moved to Las Cruces, I continued this vision quest (this quest for poems) in what most people would think was an arid land, but for me I kept seeing so much there from the tracks of insects in arroyos to the decomposing bones of animals, and it all stirred something with me.

After I left Las Cruces, I moved to Clovis on the high plains of eastern New Mexico. A different landscape, but another place where I sought to understand myself in the vast plains, the vast sky. For me, landscape is a way of going within myself. The desert, the plains, I search there to find myself.

After Clovis, I moved back to northern New Mexico, close to the mountains where I had grown up. It was like returning to old friends. Beyond Nageezi follows my journeys to the desert, the plains, and then the mountains, all of it New Mexico. The land/nature sends me deep within myself, and there I can contemplate who I am, who we are.

You’ve been selling books in Santa Fe since 1988. Has running a bookstore affected your relationship to poetry or literature in general?

My wife and I are both big readers and our bookstore, Books of Interest, provides us with an incredible selection of books to read.

But having a bookstore has had a negative effect on my publishing. Early on, I was seeing how many books are continually being published, I was seeing how many books that were read and cherished at one time are now forgotten, I was seeing how the amount of previously published books seems endless. Even with as long as I’ve been selling books, every week I see piles of books I’ve never seen before. I began to think maybe it didn’t matter if I published a book. There were so many books already. I began losing interest in publishing.

But otherwise, having a bookstore has been a life of riches, the riches of countless books. And always finding the unexpected book to read. I grew up in a house without books. I tell people that by having a bookstore I’m overcompensating for that beginning.

What are you working on now?

I’m just finishing a collection called Leaving Salida. The premise of the collection is that I’ve died, but I find myself in Salida, Colorado, living a life there, without being aware that I’ve died. But as the poetry collection progresses, I start seeing that things are not quite right. What I’m discovering with my editing is that the old poems are triggering new poems. As an example, Leaving Salida is over 100 pages long. More than 80 percent of the poems are new.

A while back, I put the finishing touches to a manuscript called Blossoms That Are Only Snow. It’s a long collection of poems dealing with where I grew up, poems about family and the culture I grew up in. Poems about the ending of a community, of a time. I think of the collection as cathartic.

I’m also putting the finishing touches to a collection of story poems, vignettes of the west, called What’s West, Anyway?

Bonus question: In her foreword, Joy Harjo shares a delightful memory of your contribution to her Thanksgiving dinner. Do you have any memories or anecdotes of her you’d be willing to share?

I went to the University of New Mexico in a program called Upward Bound. About a month before graduating from high school, I had no plans to go to college. There was no money to go to college, and I didn’t know anything about scholarships. A school counselor called me into his office and asked me what I planned to do after graduation. I told him I had no plans. What would have happened is I would have been drafted and sent to Vietnam. That’s what happened to my best friend. The counselor swiveled his chair to the waste basket and picked up a letter. It was about a new program at the University of New Mexico. He asked if I wanted to apply for the program. I certainly did. I got accepted into the program. The students in the program attended a summer session, right after high school graduation, to help us catch up with other entering college students who had gone to better schools. A counselor in the program who I became friends with was Simon Ortiz, who has since become a well-known writer. When we met, he still hadn’t published a book. A year later, I was walking along Central Avenue in Albuquerque and saw Simon sitting at a bus stop reading a book. “Simon!” I said. I hadn’t seen him in a while. He looked up from his book and when he saw who I was he jumped up and said I had to meet someone he was living with. The house was nearby. It was right on Central and next to Interstate 25, which went over Central. We entered the small house, and I saw a young woman about my age sitting at a typewriter at the kitchen table typing something. Simon went right up to Joy and told her he wanted to introduce her to “Pablo Neruda.” Whenever he called me Pablo Neruda I thought Simon was making fun of me, but years later, Joy told me that wasn’t the case. When Simon went into another room, I saw that Joy had been writing a poem, and I felt bad about interrupting her in the middle of it. But Joy didn’t seem too put out by the interruption, and we had a conversation. Joy said that she had wanted to be a painter and had gone to the Indian school in Santa Fe to study art, but she had met Simon at a party and under his influence she was now writing poetry. Later on, Simon, Joy, and I would exchange poems. It was a growth progress. Three poets without a book to their name.

Born in 1950 in Chacón, New Mexico, poet Leo Romero is considered a foundational figure of Latino letters. He holds an MA in English from New Mexico State University. He has worked for the Social Security Administration and the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Since 1988, he has been a bookseller in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He’s had five different bookstores at different times. His current bookstore is Books of Interest. Romero has published six books of poetry and a book of short fiction, Rita and Los Angeles. Romero’s poetry has been published in Italy, Germany, and Mexico. The Group Theatre Company in Seattle, Washington, produced a play called I Am Celso, based on poems from Romero’s books Celso and Agua Negra and performed it across the country. Romero received a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship in poetry, was a Pushcart Prize winner, and a Helene Wurlitzer Foundation resident at Taos, New Mexico.

The University of Arizona Press

The University of Arizona Press